By Indranie Deolall

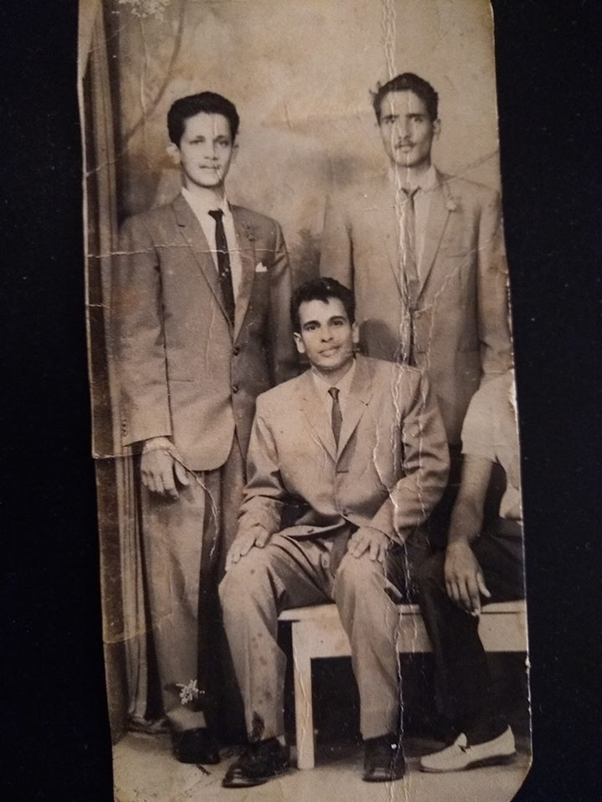

They came for my laughing father late one evening. Dad was playing dominoes with jolly friends outside, in the yard, as he did most afternoons after construction work, slamming the tiles with such force, the makeshift table that was really a leftover slab of peeling, painted plyboard, shivered for a second, sprung up and settled back down, shaking with surprise.

One player crouched at the top of the short, wooden steps my dedicated mother had hand-scraped and scrubbed to a sheen, studying his pieces and next moves, while bracing back on the closed double panelled door. Perched on our prized vintage Bentwood spindle-back chairs borrowed from our tiny kitchen and living room, the others concentrated on their hands, unable to believe shrewd Dad had strategically blocked them at both ends in the game variation chosen that day. Invariably, we would hear the grudging repeat concession from the cornered pair or three, “RAP, RAP, RAP.”

Our father would lean over and move in for the final deafening blows, delivered with the confident staccato display of the seasoned champion while delivering a comic commentary that concluded only when his tiles were all on the board. His shocked foes would stare in disbelief before bursting out in guffaws. “Raz’r boy” they would break the tension, shaking their heads in admiration, using an affectionate nickname that celebrated his biting wit and sport sharpness.

Comedian chuckled

The group of policemen showed no identification or warrant. Always the comedian, my disbelieving father, chuckled and continued with his dominoes, unwilling to abandon a favourite game. He waved them on to search the few small rooms we occupied in the sectioned rental apartments of the former stately home that had fallen on hard times. They demanded my startled, petite mother open our lone wardrobe ignoring her defiant request for an explanation, while my siblings looked on struggling to make sense of the bizarre intrusion.

By the time I received the message at my aunt’s home in the next street of Middle Road, La Penitence, in Georgetown, they had already hauled away my protesting father in their vehicle. In the dusk, I remember frantically running along the connecting lane to Albouystown that remained a hazardous brick-strewn muddle of potholes even in the dry season. My traumatised mother was inconsolable, crying plaintively, the neighbours standing around her wide-eyed and whispering. Homework lay abandoned on the desk, the dominoes scattered and upturned across the table, the empty chairs still outside, and my father’s friends and the older of my two brothers were off to try and find him.

Numb and incredulous

Our home was in an unprecedented mess. All the drawers had been opened and ransacked, the few pieces of dress clothing my family owned and kept for special occasions lay strewn on the floor, the couple of cardboard boxes hauled out from under the metal beds. Even mom’s Hindu altar and my father’s prized collection of silver trophies for dominoes and pools had not been spared, the covers separated from the cups, the remainder thrown off the bases and stands.

I stood on the deteriorating bridge outside the rusting gates, cold, numb and incredulous, hugging my chest and staring at the stars, helpless and afraid, pacing and waiting for word, thinking of the tyrant who had made himself executive president and who ruled us with an iron fist. Remembering the immortal poetry of Martin Carter whose words became so real to me, I thought of those who had disappeared in the sporadic unrest. Others had recently been slaughtered like the brilliant historian and political activist Dr Walter Rodney, assassinated on June 13, 1980, the eve of my 13th birthday.

Unable to sleep or cry, exhausted and worried, we gathered as if preparing for a wake, jumping up to peer through the windows into the late, inscrutable night. A poor family, we had no weighty godfathers or political contacts to beg for assistance and information. Neither of my parents or any of us belonged to a political party.

Beaten badly

A day would pass before we learned our father had been detained and kept in custody. The next time I saw him, he could barely walk and had to be helped from the car and through the gates and door. Dad had been beaten so badly; his face was swollen beyond recognition, his head cut from the repeated gun-butting; the bloodshot eyes, mere slits, the mouth, a fat grimace. He had been taken by the forces to a lonely area near to a canefield, tortured, pummelled and kicked to the ground, his testicles hammered until he passed out, his screams and insistent denials further enraging his attackers and echoing in the emptiness of the back dam. They stuck the weapon into his mouth and mocked that they could kill him and no one would ever find his body.

By the time we got him back, he was vomiting blood, his body was black and blue, and the trademark chortle had evaporated. The private doctor gave him painkillers and told him he was lucky to be alive without major broken bones after such a battering. Our mother did her best to physically patch him up, sapping the wounds with warm water, feeding him soup, as he winced and pushed the spoon away. We fussed over him, as he tried to smile at us, a grotesque representation of the man we had known, and the parent we had nearly lost.

Mixed-up addresses

Eventually, we would learn that the dreaded black clothes squad had no name and mixed up the numbered addresses. They had been searching for our neighbour, according to a description provided by some unknown aggrieved party, at 314 Independence Boulevard, across the road on the eastern side of us. Instead, they had come to 315 Independence Boulevard, and found our father, also of Indian ethnicity, but darker and much older.

The guilty individual’s crime was purchasing a stolen VCR. On seeing the Police at our home, he had quickly bundled his wife and child into his car and fled the city for the far side of the eastern county of Berbice, headed if need be to neighbouring Suriname. We did not even own a television set.

My father changed, the light went out of the distinct gray-brown eyes, the smiles grew subdued, the dominoes, quieter, and he urged my sister and me, his two girls, bluntly, to get out while we still could. When I later turned down the marriage proposals of overseas-based Guyanese strangers, who had sent representatives to my parents, Dad asked me, his eldest child, if I was sure that I wanted to stay put, single, and to continue working at the State-owned Guyana Chronicle.

His marriage to my mother had been arranged, like his parents, and grandparents, and our ancestors before them. Dad would be felled a few years later not by a policeman’s boots but by a massive heart attack at 47, on July 24, 1989, when he and my mother marked their 23 wedding anniversary, a day after their older son turned 21.

*ID watches her grown Barbadian children play dominoes after she told them some of the stories of their grandparents. The immortal lines of “This is the dark my love” by Martin Carter, is seared into her brain, but especially on Father’s Day.