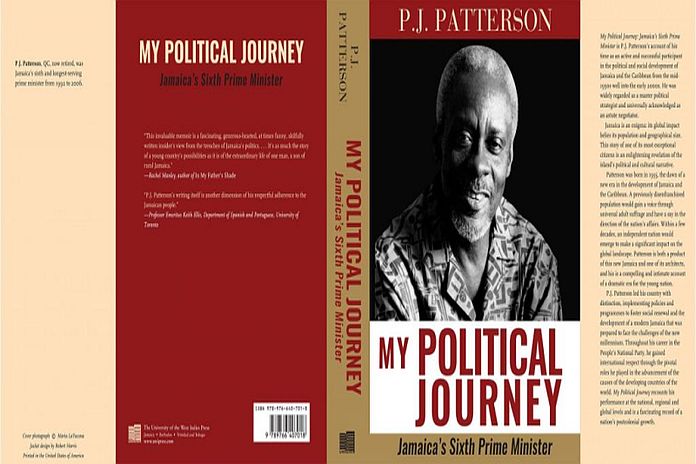

This is an edited version of the address delivered at the book launch held at the OAS Headquarters, Washington, DC, on 13 March 2019.

A review by Sir Ronald Sanders

This was a journey foretold. In 1962, the Lancaster House Conference in London on Jamaica’s independence had concluded, and Norman Washington Manley had just taken off for Jamaica aboard what was then a BOAC flight. He remarked to colleagues: “We have just left a future prime minister on the ground.”

The person to whom Norman Manley referred was P.J. Patterson, then reading for the law in London, but already an activist politician for the People’s National Party (PNP). Norman Manley’s very accurate prediction in 1962 was unlike that of Bruce Golding’s some twenty-seven years later when Manley’s forecast came through, and P.J. took up the baton of leader of the PNP and prime minister of his nation. According to Golding, then chairman of the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP), the PNP had selected “a boy to do a man’s job”.

Few politicians, in their exuberance to belittle their opponents, have been proven as wrong as Golding. P.J. not only performed manfully as prime minister, he became the first person in Jamaica to lead his party to three consecutive election victories and to set a record for serving as its leader for fourteen years. No one else, in the past, had won such confidence by the Jamaican people, and it is doubtful that any one will in the future. Norman Manley knew what he was talking about.

Of course, P.J.’s political journey, lucidly and entertainingly recounted in his book, did not begin in March 1989, when the mantle of prime minister was placed upon his shoulders. It is difficult to think of any political leader anywhere in the entire world who had been better prepared for the qualities, comprehension and disposition to be a leader at the apex of a nation’s affairs. He had served as minister of industry, trade and tourism; deputy prime minister and minister of foreign affairs and foreign trade; deputy prime minister and minister of development, planning and production; and deputy prime minister and minister of finance and planning. And, in between, he served in Opposition – in the senate and outside of the legislature; and in the councils of the people’s parliament conducted in villages across Jamaica.

That impressive list of ministerial portfolios tells a bare-bones story of political progress. Remarkable though it is; the list does not convey the human tale: the beginnings in a rural village; the thirst for education; winning scholarships that made such education possible; the natural intellectual attributes that marked him for a bright future; the openness of his personality; the deep commitment to the improvement of the lives of his people; his unconditional love of his native land; and his devotion to the idea of a diverse but single Caribbean society. It is to his contributions to the wider Caribbean that I now turn.

For, it is those contributions that inspired a generation of West Indians like me who were privileged for over four decades to marvel at his genius, to learn from his bargaining skills and, more than anything else, to believe decisively and resolutely in the worthiness of the Caribbean people to command respect in the world.

In this regard, P.J. was in the company of a group of his compatriots that everyone knew to be West Indian but few could recall the exact country of their birth – such was the depth and quality of their service to the region and their unwavering belief in the strength that unity brings. Among those persons are Sir Shridath Ramphal, Sir Alister McIntyre, William Demas – all labourers in the vineyard of the Caribbean’s development.

In 2006, P.J. received the accolade of the Chancellor’s medal from the hands of the then chancellor of the University of the West Indies, Sir George Alleyne – another outstanding and distinguished Caribbean son. In accepting the medal, P.J. delivered a message to the entire Caribbean. He said: “We cannot allow ourselves to be swept away by the tide of a passive acceptance of globalisation or ignore the real opportunities to tell our Caribbean story and assert our rights in various international organisations to which we belong.” Those words resound with a compelling freshness and significance today as the Caribbean is beset by forces that seek to marginalise our region, to deprive us of a voice in global affairs that materially affect us and to treat our small, individual territories as annoying complications.

In his book, P.J. summons us all, time and again, to resist such relegation and to adhere to the value of joint and collective action by Caribbean nations. He says, for instance: “The assertion of our united voice as sovereign nations singing from the same hymn sheet is the only way for us to be heard in the global din”. And, he knows with authenticity, born of lived experience, of the truth of which he speaks. P.J. was an integral participant in the most significant demonstration of unity by developing states at a significant crossroads of their fortunes.

Ironically, given today’s Brexit where the UK is seeking to break away from the other twenty-seven nations of European Union with no clear roadmap for its future, it was the UK’s decision to join the European Union in 1973 that occasioned the unification of African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries to negotiate a trade and development agreement with the European Economic Community (EEC). The arrangement involved three regions, but one voice on each aspect of the negotiating pillars. The Caribbean’s main spokespersons on behalf of the ACP group were Ramphal and Patterson.

Many lessons arose for the Caribbean from those negotiations, not least that the unity of developing countries is a formidable force in bargaining with other countries and regions, much bigger and powerful than themselves. It is no exaggeration to say that the Lomé Convention that emerged from those ACP-EEC negotiations continues to stand today as the most beneficial trade and development document ever signed by developing states.

Another lesson is that, in international bargaining, it is sometimes necessary to stand up vigorously for Caribbean rights: to let slip the agreeable countenance of diplomacy in the face of downright bullying and show our mettle. P.J. tells the story, for instance, that in the closing days of the ACP-EEC negotiations over sugar, the divide was wide and the tensions high. “So much so”, he says, that he and his counterpart, the EEC commissioner for agriculture, “almost came to blows”.

But this virulent standing up for Caribbean rights became a matter of deep respect by the EEC. Today, there is in the headquarters of the European Union in Brussels, a Patterson-Ramphal room so named by the Europeans themselves in honour of these two outstanding West Indian champions with whom they had to contend.

P.J. Patterson is a lawyer and a good one. His political life adhered to two fundamental principles both at home in Jamaica and on the wider global stage on which he acted in Jamaica’s and the Caribbean’s interests. Those principles are respect for democracy and upholding the rule of law. He maintained these values in his political life in Jamaica and he championed them in every international forum on which he appeared. In his own words:

While small and powerless states do not in fact receive equal treatment in the application of international law, we in the Caribbean who lack military power are nevertheless compelled to continue the search for that ideal in which the international system will uphold right over might and law over force.

That is wisdom from an authentic voice speaking from Caribbean trenches in international battlegrounds that have not diminished; they have simply appeared in other forms: (a) in the EU blacklisting Caribbean countries in language that pretends cooperation but actions that manifest coercion; (b) in the World Trade Organization where big countries deny justice to small ones; (c) in the Organization of American States where, after more than fifty years of membership, our development aspirations still play second fiddle to the political ambitions of others; and (d) in the lip service paid to the adverse effects of climate change that point like a dagger at the heart of our existence.

In all of this, as P.J. has long and often advocated: “There is an urgent need to create a cohesive and effective strategic alliance among small developing economies” And such an alliance must be cemented first among the countries of the Caribbean. P.J. says this of himself: “Pride and loyalty to the land of my birth have never deterred me from becoming and remaining an unrepentant regionalist”. Persons, like me, have been eyewitnesses to both those fervent commitments.

P.J. played decisive roles in deepening Caribbean integration and, importantly, in maintaining it. He did so in many remarkable ways. And I will relate one story, not included in the book, that illustrates the unique role he played. At a certain CARICOM heads of government conference, angry disagreement between two prime ministers became so intense that the possibility of fisticuffs loomed large. P.J., with the authority only he could exercise, lodged himself between the two men, shouting and gesticulating at each other, and in his persuasive but powerful style, calmed the tempers and cooled the temperature.

Just to be sure that peace would continue to prevail, P.J. spent most of the conference, not at his seat before the Jamaica flag, but in a chair between the two prime ministers, engaging them in friendly banter and discussion that focused their attention on the real issues at hand. In this and many other unique ways, P.J. Patterson helped to hold our region together, concentrating not on transient differences that could divide us, but on the greater unity that can strengthen us.

There is much more that could be said of P.J.: the role he played in the Commonwealth and in the fight against apartheid in South Africa; his stand on principle with Cuba; his resistance to pressure over Haiti and the devious removal of Jean-Bertrand Aristide in service to external agendas – for he played a part in all that – and more. For a generation of persons who dedicate their lives to public service, we are privileged to have witnessed P.J. Patterson in action and to be inspired by the high quality of his leadership.

He makes us all proud to be West Indian and inspires us to summon the best of ourselves in service to our region. His book is compulsory reading for all who aspire to leadership and even those entrusted with leadership today.